In my last post, I made the case for big, bold fundraising campaigns and why you need to be in one. The main reason, of course, is to maximize your organization’s philanthropic potential and do something big to advance your mission. Beyond that, however, a campaign can catalyze other benefits, including increased awareness, new relationships, an elevated culture of philanthropy, and energized stakeholders.

So, revisit that post for the why.

This post is about getting started—the how. If you’re not currently in a campaign, what are the first steps?

The Big Three: Vision, Cost, Timeline

First and foremost, you need a vision. And it has to be compelling.

What do you want to accomplish? What difference will it for the people you serve? How about for your organization as a whole? More than anything else, your campaign’s success will hinge on your answers to these questions.

Next, how much will it cost?

What’s the dollar amount attached to realizing this vision? And don’t just guess here. Do the legwork; get some real numbers. A range is fine to start. For example, if you want to build a new building, it’s OK if initial estimates come it at $40-50 million. Be conservative; use the higher number as a ballpark figure and then refine your estimate as you progress. And don’t forget to build in expenses related the campaign itself. For example, plan ahead for additional fundraising and marketing costs.

Why is articulating a price tag so important at this stage?

Because clarity inspires confidence. It shows you’re serious about achieving your vision and that you’ve done your homework. I’ll contrast that with two approaches you definitely want to avoid: 1) “We just want raise as much as we can,” or 2) “We’ll scale the project according to people’s willingness to give.” These reactive, rather than proactive, approaches do not inspire confidence or get donors excited. Base your campaign goal on the real costs associated with achieving real outcomes.

Another critical piece: a deadline.

You don’t have a fully-formed campaign unless you have a deadline. When do you need to raise the money so you can realize your vision? Urgency is a campaign’s best friend. Without a deadline, you don’t have it.

Getting Buy-in

Some boards will lead the way and push the organization to start a campaign. Other boards will avoid the “C word” because they know it means they’ll be expected to give generously.

It certainly helps accelerate buy-in when the board leads. Because whether they lead or follow, you need your board on board! In fact, a good chunk of the overall giving should come from your board.

So, what do you do if your board isn’t leading the way. How do you get the buy-in you’ll need under these circumstances?

Well, before even proposing a campaign to your board, you’re going to want to make sure you have sufficient buy-in within the organization’s leadership, at least on a conceptual level. The earlier you can achieve alignment between the CEO, CFO, and CAO (titles will vary) on the broad contours of a proposed campaign, the better.

The next group to engage is the remainder of your organization’s senior administration. And then, finally, the leaders of any programatic areas that the campaign will impact. For example, if your campaign will build athletic facilities at a college or university, you’ll want to include key members of the athletic administration.

With sufficient internal alignment (again, largely big picture at this stage), the CEO will be well-positioned to begin a dialogue with his chairman.

The chairman and the CEO can then work together to expand the circle of buy-in from Executive Committee to other relevant board sub-committees and then to the full board. Whenever possible, you want to leverage your board’s leadership to secure buy-in from the rest of your board.

Ideally, this process doubles as cultivation of your board members for their own campaign gifts. Make sure, whether through a formal feasibility study, committee meetings, or peer-to-peer conversations, they have an opportunity to offer their feedback on the campaign’s case for support, fundraising goal, and timeline.

All of this is important because your board will ultimately need to approve your campaign. This critical moment and should come with a lot of excitement. And, in embracing their role as decision-makers, members of your board should also be eager to be the first to pledge their support for the campaign. Build buy-in effectively and you’ll be off to a great start.

Case for Support

A campaign’s Case for Support is essentially its reason for being. In it, you articulate a vision—a new future for the constituents you serve. It’s a core statement and you’re going to use it everywhere, including in printed materials and on your website. And, ideally, you’re able to distill it down to an “elevator pitch” that every staff member and volunteer working for the organization knows by heart.

There are plenty of great firms out there that can help you develop a case that’s right for your organization and even write the copy for you. You can also develop this internally if you have the right expertise on staff.

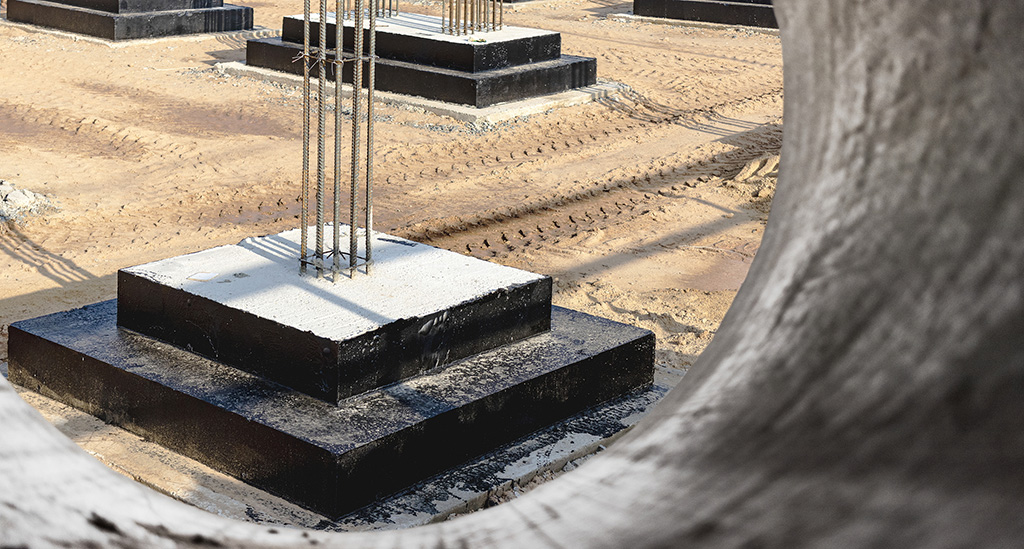

Regardless of how your campaign materials come together, they needs to look good. Now, we’re not talking museum quality artwork here, but your marketing pieces do need to look like you’re serious about your campaign.

And your case should be written in plain English. Avoid jargon. Your vision and aspirations need to shine through. Don’t lose them amidst florid language.

Also, you don’t need to cover all of the details in your case. Stick to the headlines. And tell a story. People are more likely to read or watch something if they’re engaged in a compelling narrative. Center the donor in this story—make them the hero. After all, they share the hopes, dreams, and aspirations of your organization. Focus on the bright future your campaign will allow the two of your to create together.

Make sure your case isn’t written in a vacuum. Invite feedback from key stakeholders, including campaign leadership, relevant program staff, your organization’s Advancement Committee, and perhaps others. Now, I’m not suggesting you let all of these folks edit copy; that will get tedious, and fast. But do solicit their feedback. If they don’t find your draft compelling, you will have a hard time connecting with less-engaged prospects.

A “feasibility study” is also a great opportunity to take your case for support for a test drive. Campaign feasibility studies are typically conducted by an independent third party such as a philanthropy consulting firm. The firm interviews key donors to get a sense for whether your case for support resonates with them and if they are likely to support the eventual campaign. They are also helpful in validating (or invalidating) a campaign’s potential goal.

Feasibility studies are a hot topic right now, with many in the non-profit world asking “Are they really necessary?” I’ll share my thoughts on this question in greater detail in the next post in this series on campaigns.

We’re going to leave this one here for now. We’ve covered the essentials needed to start your next campaign—to turn an idea into action. You need a vision, you need to know how much it costs, and you need a deadline. That should be enough to help you secure initial buy-in, develop a written case for support, and position your organization to take further steps.

The next article in the series will focus on campaign readiness, including validating your case, building internal capacity, and making sure you have the resources you need to be successful. Stay tuned.

Leave a Reply